Exploring the “Georgian-ness” in between knitting needles

by Qiaoyun Peng

Graduate student. Central and East European Studies, University of Glasgow

Current research focuses on the knitting tradition and national identity of Estonia.

When I first arrived in Georgia, I had not expected to find a rich knitting tradition there.

Arriving in Kutaisi at midnight, after two transfers and a long flight, I found the warm wind from the Black Sea there to welcome me, blowing through my hair. Georgia, a small country located in the southern Caucasus mountains, has been described in such terms as ‘on the margins of Europe’, ‘a cradle of wines’, and ‘mountains of poetry’. It is famous for its unparalleled Caucasian hospitality, delicious food which was once widely welcomed by the people of the Soviet Union, and its amazing natural beauty which has been warmly praised in poetry.

I got my passport stamped, wandered around the small airport, trying hard to search for key words from my limited knowledge of Georgian culture. That’s the moment when I got my first 10 Lari note in a small cafe. I was not very awake; I almost fell asleep on my hiking backpack from exhaustion. The 10 Lari note piqued my interest immediately and kept me alert:

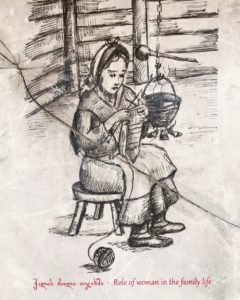

The figure on the 10 Lari note is a woman, sitting and spinning yarn, a perfect symbolical link with my career as a knitting expert-in-training.

‘Ah, maybe that’s the very reason why I ended up here.’ I said to myself, rubbing my sleepy eyes as I emerged from the airport.

(Georgian banknote, 10 Lari)

Later on, at the Tbilisi Open Air Museum of Ethnography, I met a museum member of staff sitting in that very pose depicted on the banknote, knitting. People are specifically engaged to do this in ethnographic museums: to recreate the historical life scenes. Apart from this ‘alive banknote scene’, on a cradle for newborns, I also found the object, which is on the 10-Lari-note-lady’s lap, in the middle of a traditional Georgian house.

(Crocheted baby shawl, Tbilisi Open Air Museum of Ethnography)

All these things set up for me a scene of old golden days in pastoral poetry. And even for a graduate student, like me, doing knitting studies, Georgian knitting is a New World. Before I came to Georgia, I got a book named ‘Politics and Identities in the Baltic and South Caucasian States’ from my supervisor’s magical bookshelves – originally, I picked it up for Estonian knitting, but surprisingly, it seems fortuitous for my discovery in Georgia. Not to mention the Tbilisi Open Air Museum of Ethnography which reminds me of its ‘sister’ in Riga all the time when I was there.

It seems, however, that the Baltic States have done better promotional work for the knitting tradition than Georgia. While the book of Latvian mittens has been translated into many languages and therefore attracted lots of tourists to go for a knitting-themed trip in Riga and Liepaja, there are many fewer visitors to the open air museum in Tbilisi – and that may be one of the reasons why their knitting workshop closed during the summer period, which should be a busy season for foreign visitors.

(Knitting workshop, Tbilisi Open Air Museum of Ethnography)

Although Sofia Tchkonia, founder of the Tbilisi Fashion Week, describes Georgian knitwear as ‘the Missoni of the mountains’, and it should be considered as some of the best in the market, Georgian knitting is far from being famous outside the country itself. I have no memory of reading relevant articles during my work on the literature review of my ongoing knitting research project. And when I reviewed the book ‘Knitting Around the World’, it includes no section about the Georgian knitting.

In the Baltic States, knitting tradition has been well-promoted as a part of their handicraft heritage. Walking in the town centre of Tartu, it is easy to notice that nearly every souvenir shop has a ‘käsitöö’ (handicraft) mark on the signboard. The famous Haapsalu lace shawls are packed in small boxes with a short description, ready for tourists to upgrade their ‘Estonian-ness’. You can buy a box of Latvian yarn in the old town of Riga with the slogan ‘knit like a Latvian’, or go for a knitting camp in Liepaja, the city located on the shore of the Baltic Sea. However, things are different in Georgia. I was educated in the Khevsurian knitting tradition only by an old lady I met at random in a Tbilisi tunnel. There are colourful knitted socks everywhere in souvenir shops, but the promotion of this unique culture to foreign visitors, most of whom are likely to know little about the knitting tradition in Georgia, is still waiting for more attention and bigger efforts.

(Knitted objects, Sairme, west part of Georgia)

(Khevsurian socks)

The Khevsurian knitting tradition could be the highlight of Georgian knitting in general, just like the Haapsalu lace for Estonia, mittens for Latvia, and the Fair Isle technique for Scotland. Living in the mountainous area of the eastern Georgia, sharing borders with Chechnya, Khevsurians managed to preserve their unique culture partly because of their isolation. A long history of breeding the Tushetian sheep is another key factor: the adequate supply of wool ensures the material basis of knitting tradition. Touching the Tushetian wool reminds me of Shetland wool – neither is very smooth, but even a little bit rough. This kind of wool, however, is ideal for combining colours and could be very warm, perfect for tough weather on the isles and in the mountains.

Knitting is usually considered as women’s work. During the research I encountered the gender factor. When I first started to pay extra attention to the Georgian knitting tradition, meaning having random talks with random Georgian people working in the museum, the information which I gathered confirmed my hypothesis. Knitting, as a part of traditional housework, is being promoted as an indispensable part of ‘women’s work’.

(A picture of knitting in the Open-Air museum of Tbilisi)

Nonetheless, when I started to browse different online resources on Georgian knitting, it took me only few seconds to find an interesting piece of news:

“Knitting philosopher wins Georgian presidential vote.”

Yes, Giorgi Margvelashvili, the president of Georgia, a typical burly Caucasian, is a knitter. This should not be unexpected if we return to the very beginning of the knitting tradition. According to the Penguin Knitting Book (1957), in ancient times, knitting craft was carried out entirely by the men-folk. It has slowly evolved into a typical ‘women’s work’ in the historical process, and now has become a gender stereotype of the ‘femininity’. The self-image construction of Margvelashvili being a knitter-president could be explained as a promotion of ‘Georgianess’, showing his will to preserve Georgia’s knitting tradition: a culture which is important enough to be put on the national currency.

(Georgia’s knitter-president Giorgi Margvelashvili, image from the internet)

I decided not to spend that 10 Lari ‘yarn-note’ and kept it carefully as one of the most precious souvenirs of my first trip to Georgia. This discovery of the hidden beauty in the mountains has left many unanswered questions to me. Could it be possible to promote the Georgian knitting tradition on the basis of an existing successful model, the Baltic knitting? How can we generate the most benefit to tourism through knitting culture? What is the best way to combine the traditional knitting pattern with the modern design? A shortage of time and other limitations, unfortunately, allow me only a shallow understanding of the Georgian knitting culture. I have not managed to research it more deeply so far. With the Georgian yarn note in my wallet, however, I am sure that someday in the future I will be back for a proper research trip to the Khevsureti area, where colourful socks are knitted from generation to generation, far into the mountains.

————————————————————————————————————————